Dear Cathedral Arts Blog Reader:

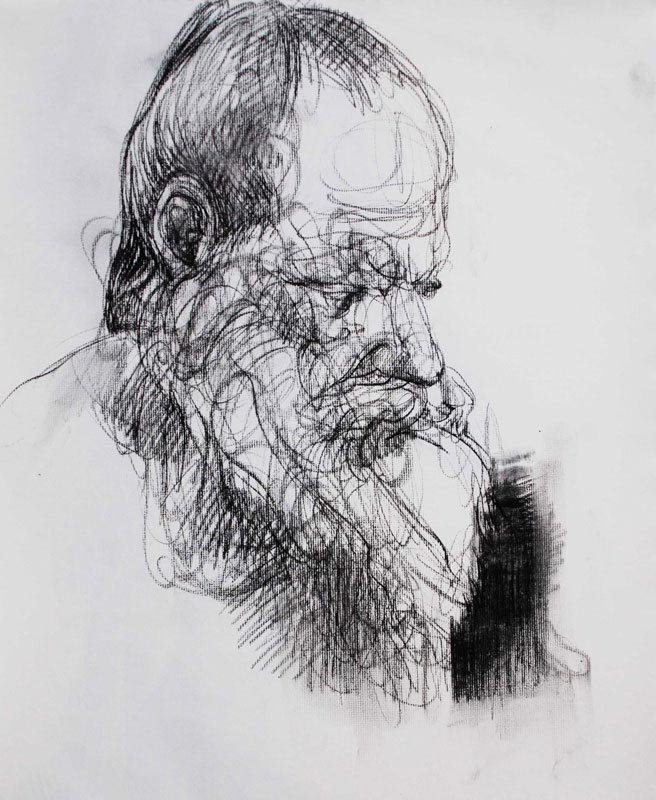

It has been a while since I have written, while our vocation of faith and art is my mind and heart as I undergo formation as a hospital chaplain resident, a role I began at the end of August. This work is many things for me–one is an affirmation of what I learned through beginning the Cathedral Arts program five years ago—that my study of the human form as an artist and our work of beauty in worship has everything to do with my ability to offer healing through spiritual conversation. Below is a study of a model I made many years ago which I call, “Mariner,” as I was listening to Coleridge’s poem while I made it.

Remembering for moving forward—we have reflected on how the Logos, the Word of God, in poetical early Christian and ancient-world thinking was intimately connected with the concept of Image, or Ikon in Greek. I have made recent attempts, bringing you with me, at understanding iconography in the Eastern Orthodox tradition which depicts Christ and the saints. A contemporary iconographer, Christine Hales, publishes an in-depth blog for those who wish to learn more about icons as Christian art and prayer HERE.

The liturgical arts workshop at the Chichester Cathedral has also come to my attention–read about this HERE in the Orthodox Arts Journal.

Recently, the Cathedral welcomed Malcolm Guite to speak on the Psalms with his own poetry made in meditative response to them. His scholarship and creative work seeks to help the church recover its imagination and thereby its God-given power. His course called Lifting the Veil: Imagination & The Kingdom of God is being offered by Nashotah House Theological Seminary for free HERE:

A few weeks ago, I was to give the talks at the retreat for the Daughters of the King. Finding it difficult to emerge from the primordial ooze one’s mind returns to when starting a new role–particularly one that is emotionally and spiritually demanding–-to write something meditative and comprehensible, Julian of Norwich (to whose order I had made a commitment exactly two years earlier) rescued me in saintly fashion.

The theme of the workshop was “Behold.” In pursuing the roots of this Old English word, much-favored by early English Bible translators and also by Julian in her book, Revelations of Divine Love. I read what Denys Turner of Yale writes in his book, Julian of Norwich, Theologian, that Julian would have been familiar with the stages of lectio divina (lectio, oratio, meditatio, contemplatio), and that her book would have better been called Meditations on Divine Love.

And that for Julian, beseeking (or beseeching) was oratio–what we might call intercessory prayer, born of the desire God put in our hearts. And, Turner writes, for Julian the last step of prayer is beholding corresponding to contemplatio in the stages of lectio divina.

Julian affirmed my vocation of beholding—beholding those who are in danger of feeling lost in life’s liminalities and reflecting what I see that is good, true and beautiful back to them—beholding faith in art and art in faith within the life of the Cathedral. Through contemplation with Julian my proverbial tongue was loosened, and I was able to see and share art again.

I showed the Daughters this medal below, made in England during Julian’s lifetime for one on pilgrimage. The animate willingness of the bird-like figure makes me think of the words in the collect: “Lord Jesus Christ, you stretched out your arms of love on the hard wood of the Cross that everyone might come within the reach of your saving embrace……”

And I shared this image below from a Spanish mural of the 12th century which is at the Cloisters in New York City. Medievals supposed lions wiped out their tracks with their long tails. This is Christ, who gained victory over sin and death by hiding his true identity from the devil and tricking him into bringing about his death for the salvation of humankind. Will your modern imagination allow you to see this cat with a hipster mustache as Christ?

This symbol of Christ was painted a couple hundred years before Julian had her visions while plague caused widespread suffering. During these years the prevalent image of Christ shifted from the victor over sin and death to sacrificial victim. Julian’s vivid visions begun with Christ bleeding out on the cross and her subsequent meditations on them led her into deep contemplation of God’s love where she ends by declaring, “Love was His meaning.”

A week and a half ago I went to New York again to the Neue Gallery to see the exhibit MAX BECKMANN: THE FORMATIVE YEARS, 1915-1925 up through January 15, 2024. But first, I walked through the permanent collection, and was arrested by a portrait by Oskar Kokoshka.

For me it was a matter of beholding—this painting is barely more than line and dry-brushed pigment with which a human hand is formed, gesticulating in its space with profound and simple expression. For me, even though the sitter is engaged in an unhealthy modern habit, the painting is like a parable of Jesus about a woman sweeping or kneading bread because of how it bears attentive witness to the human.

For me, seeing that painting was like seeing the human hand in cave paintings, and I felt I remembered what art is. Then I was ready to walk into the first gallery with Max Beckmann's paintings. This Descent From the Cross is on the wall across from the bench on which I sunk.

I examined the shapes, color, and the artist’s drawing of human bodies from shockingly assembled disparate views as if they had been dropped from the sky and put back together. I wondered over the artist's intention described in the quote on the wall–to make a “new church” through his work, having witnessed the horrors of the first WWI as a volunteer nurse and determined to paint as an artist of his time in the face of the horror he saw coming.

I beheld the heart and mind of the artist through his representation of the human body in space and time. I felt time to be as it was described by the early prince of modern people, “out of joint.” Hamlet said this while meditating on the murder of his father by his uncle and planning retribution. The time is out of joint: O cursed spite / That ever I was born to set it right.

We are superstitious these days, believing we were born to merely set things right rather than for love and beauty. We see the time as out of joint rather than ourselves as out of joint. The poet and painter constructed worlds for modern characters in claustrophobic scenes with twisted space and reasoning. The deed already done in Beckmann’s paintings is in Shakespeare’s Hamlet the human psyche breaking and losing its capacity for beauty:

I have of late--but

wherefore I know not--lost all my mirth, forgone all

custom of exercises; and indeed it goes so heavily

with my disposition that this goodly frame, the

earth, seems to me a sterile promontory, this most

excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave

o'erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted

with golden fire, why, it appears no other thing to

me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours.

This speech became a ballad in the 60’s musical Hair which I sang with my parents’ vinyl record as a teenager and recently again while I emptied their house. I also embrace what it says in Ecclesiastes—The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning; but the heart of fools is in the house of mirth. But I know from experience that where mirth is lost madness is near. If we sing, even of our imagination for beauty being lost, we find beauty.

As Christ beholds suffering, beautiful art may be ugly as long as it is true. Beckmann's paintings may be truly representative of beauty in that they are true, exposing faulty human reasoning and cursed spite. Myself and others stunned into contemplation on the bench before them is perhaps what the artist hoped for when he wrote he wanted to make a “new church,” one that could imagine a different future than what it helped make.

The prophetic and imaginative work of bearing witness to the Image-Ikon of God and the Word-Logos of God is the work of reflecting the images and analogies of the Beautiful One we are intended to be, however bent we may be.

Advent is coming, the liturgical season which commands expectation and promises a new Adam and a new Eve. There is imagination and beauty in the church to keep us sane still. Join us for a free roots jam this Sunday, and for Handel’s Messiah on Dec. 5 and for Christmas services. Until we see you, peace be with you.