The story of the life of Moses remains forever alive and helpful to me. At first, it was about a Hebrew baby meant to die but who was adopted into privilege by Pharoah’s daughter. This seemed like the gift of faith I received unexpectedly in early life, along with the gifts of finding an excellent art mentor and the benefits of being born white and middle class—all things that made my path easy, all things I did not deserve and yet received.

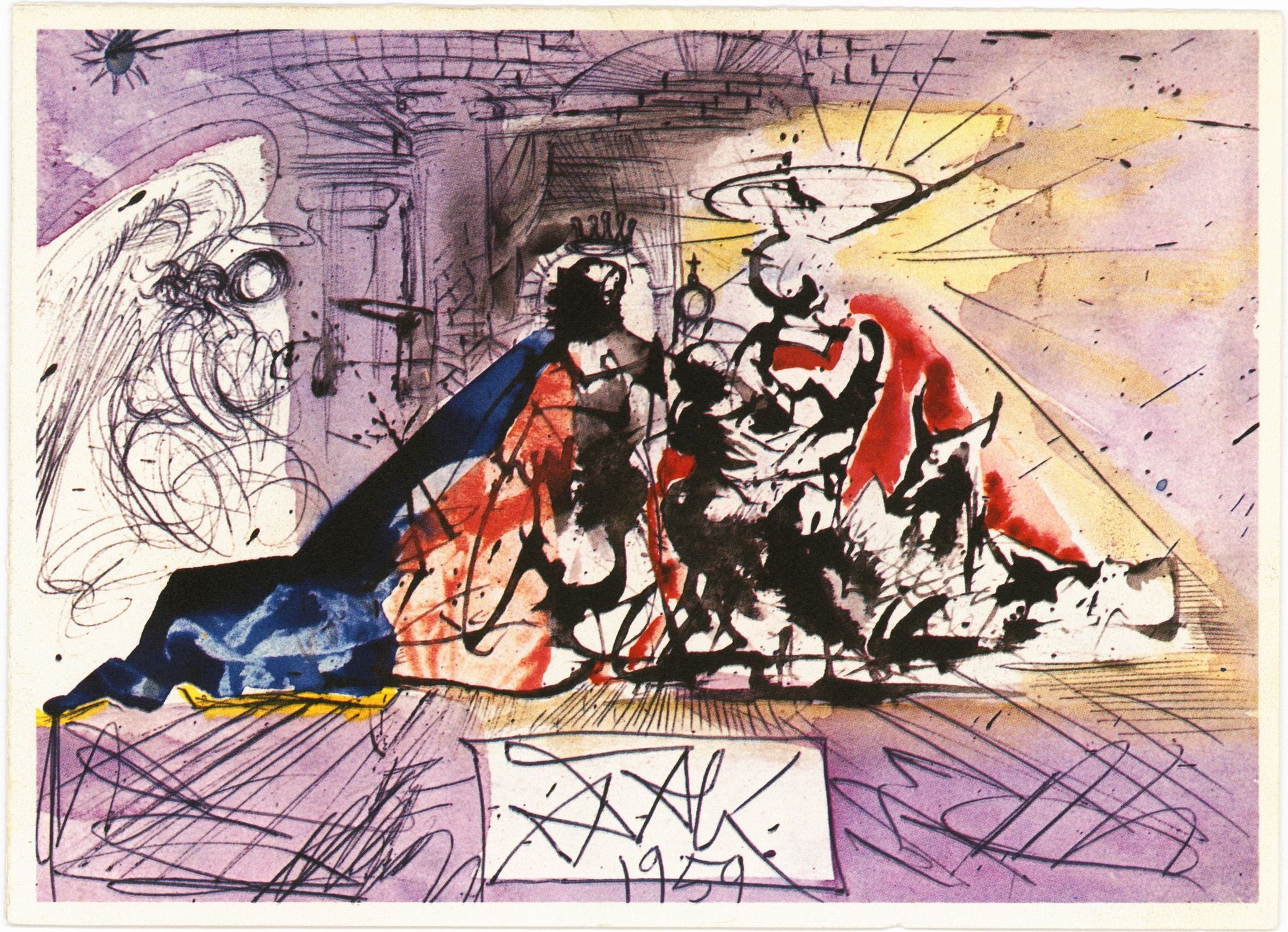

Moses seemed to be a sufferer of a perpetual identity crisis and guilt not unlike my own. After he killed an Egyptian beating an enslaved Hebrew and was discovered, Moses flew to Midian where he met the daughters of Jethro trying to water their flock, and helped them. Above is a painting of Moses with his wife, Zipporah, Jethro’s daughter, by Jacob Jordaens.

Then, forty years later, there was the matter of God calling to him from the burning bush on the mountain and the fear associated with that call—both for Moses and for me in reading about all the stages of grief leading to Moses’ acceptance through going back to Egypt to prepare Pharaoh to let his people go, and then in caring for the people in the wilderness.

To me, the couple above appear as if greeting a guest at their front door. They are for me as if I came through the wilderness and arrived in a clearing, facing them. I see on Zipporah’s face a life-long work of love and patience as her husband opens his mouth to speak, perhaps as if he will never stop, perhaps about the tablet he leans on and all it means to him.

Zipporah might be remembering when her father brought her and her sons to reunite with Moses in the wilderness after and they found him adjudicating the squabbles of every Israelite in the place. Moses loved the people, while their needs overwhelmed him. After hugs and a meal and hearing Moses out, Zipporah’s father said to him,

“The thing that you are doing is not good. You will surely wear out, both yourself and these people who are with you, for the task is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone.” (Exodus 18:17-18, NASB)

Jethro then reminded Moses that his task was to represent the people to God and teach them the law and their work, and instructed him to appoint honest men as leaders of large groups and subgroups. They were only to bother Moses with major disputes.

This reminds me of the following quote by Thomas Merton that I have been shopping around lately from his book, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander:

“There is a pervasive form of contemporary violence to which the idealist most easily succumbs: activism and overwork.

The rush and pressure of modern life are a form, perhaps the most common form, of its innate violence.

To allow oneself to be carried away by a multitude of conflicting concerns, to surrender to too many demands, to commit oneself to too many projects, to want to help everyone in everything, is to succumb to violence.

The frenzy of our activism neutralizes our work for peace. It destroys our own inner capacity for peace. It destroys the fruitfulness of our own work, because it numbs the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful.”

We may congratulate ourselves for not being unjust to others, but as Thomas Merton noted in the tradition of Jethro, idealists often succumb to violence—injustice—toward self. Somehow we often find violence toward self to be acceptable and the pain of introspection intolerable. We think we can be harsh and unloving toward ourselves and simultaneously uphold justice for others. This is what I believed for many years unconsciously.

But when we begin to see what alienates us in our lives in the light of the love of God—as if flames calling to us from an ordinary bush—we start to hope for life and growth. As Moses had Jethro, we need spiritual companions who have been obedient to their own call to help us learn to obey ours and to learn to do justice to ourselves and to others.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, who lived and died close to the life of Moses, and Thomas Merton, who some believe to have been martyred for his anti-war work, left writings and speeches which have provided many with spiritual companionship inspiring toward justice. They had their companions, such as theologian Howard Thurman, whose writing King carried along with his Bible. Merton had the desert fathers of the 4th century, among others.

There is nothing new under the sun—spiritual people grow from seeds sown by spiritual people. John Cassian (360 – c. 435), brought the teachings of the desert fathers to the West by writing in Latin. Cassian influenced Benedict of Nursia (480 – 548), whose Rule for monastics continues to guide many. Both inspired Saint Ignatius of Loyola wrote a series of spiritual exercises in 1522–1524 in which I currently engage and which, even in the great difficulty of our time and place, help me start each day with peace.

Before the Exercises begin, Ignatian teaching offers support for growing in greater recognition of God’s love and lessons in discernment. Only after the exerciser is secure in God’s love do they consider their sin. (This takes many hours, read Psalm 139 over the course of a half-hour on three different days to get a sense of being grounded in God’s love through spiritual exercise.)

The aim of the Exercises is to let go of all that does not fulfill God’s purpose. One desire we are to pray for is what some call “Ignatian indifference.” This is not indifference such as in the email signature of a former pastor of mine which reads, “Indifference is a sin.” Ignatian indifference is opposite deadly indifference in that it is fertile ground for growing in love of God and neighbor.

Ignatian indifference is peace born of struggling to desire no particular created thing, but only what is for the “greater glory of God.” If you like, you can click to see a video with the star of Silence, Andrew Garfield, and Stephen Colbert, which tells briefly how the work of Ignatius affected one actor’s life.

Now there is an opportunity with a trained spiritual director and the book The Spiritual Work of Racial Justice, beginning soon on Zoom on Tuesday evenings. I will be participating in this myself. If you are interested in joining, click here to email me, and I will put you in touch with the presenter.

This workshop will be a context for white people in particular to listen to the experiences of people of color and to do some painful introspection in the context of God’s love which gives us strength to grow toward greater justice.

Until next time, may the peace that passes all understanding guard your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus (Phil 4:6). You will need peace to approach this world with an open heart and mind.

“The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of art is not ugliness, it’s indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference.”

–Elie Wiesel